PMIM is run by veterans from all conflicts, nationalities and backgrounds. Although, the primary focus of Point Man has always been to offer spiritual healing from PTSD, Point Man today is involved in group meetings, publishing, hospital visits, conferences, supplying speakers for churches and veteran groups, welcome home projects and community support. Just about any where there are Vets there is a Point Man presence. All services offered by Point Man are free of charge.

The military teaches soldiers how to kill, how to survive, but who helps the

soldiers & their loved ones with the invisible wounds after the war is over????

More often than not it is another soldier, veteran or someone who loves one.

As the wife of a veteran (34 yrs & still going!)I believe that its very important to know that there are others out there to help.

The following resources are provided in hopes that they may help anyone in need .

Watch the full program on PBS

THE CONTRACT

Shared by a Sky Soldier

Hi Guys:

If you are one of those struggling with accepting the fact you have

PTSD, or feel guilty or embarrassed about it, or underserving of help

the government has to offer you, attached is a little ditty for you.

Smitty Out

This past week my wife and I were visited by one of our Sky Soldier

medic buddies, whom I'll call Doc Bob. Bob and his wife were down here in Florida specifically to meet with Dr. Scott Fairchild, one of the civilian guru's on PTSD. In fact, Doc Scott did much of the early

research on PTSD for the army at Walter Reed and is a recognized

authority on the illness. He has and continues to help many Sky

Soldiers and other vets from across the country, and their wives, with his PTSD evaluations and ongoing treatment. Doc Bob originally received a 10% rating years ago for PTSD. The VA later upped him to 30% then 50%, almost without argument. There, he hit a brick wall; even his DAV rep told him there's no opportunity to improve on the rating, even though Doc Bob is clearly a candidate for 100% disability.

Now Doc Bob is a bright guy, but the VA doesn't like bright guys. If

you display any normalcy to them they will simply shoot down your PTSD claim. It's unfortunate, but that's the way it is. Doc has a tendency to sit in front of the VA pysch and engage him in intellectual conversation. The VA must think, "If this guy can talk he must not be sick". Consequently, Doc Bob is stuck at 50%, even though I suspect Dr. Fairchild's assessment of the medic will indicate otherwise.

Doc Bob and I would sit on the patio here until the early morning hours talking about our war and his illness. Our record was to 3:30 a.m. one morning. Although the VA essentially threw a 50% PTSD disability rating at him, Doc continues to struggle with denial, even though his wife is abundantly aware of his illness and how it has negatively impacted and continues to impact their lives together as well as his relationships or non-relationships with others. I know about his denial, I had it for over 30 years and it is a common trait amongst our ranks.

Another PTSD related trait I personally experienced and one which may keep Doc Scott from receiving his just, due and earned disability rating and its concurrent benefits of treatment and compensation is his belief "I'm not deserving of anything from the government (VA). I see those kids coming home from the Middle East without arms and legs, they arethe deserving ones. I don't want to take anything away from them." I understand Bob's thinking, but he's entirely wrong. And, thisself-imposed hurdle can be difficult to overcome but is essential toovercome when pursuing one's PTSD or other claim with the VA. Bob has yet to understand the government has passed laws and established benefits and compensation specifically for him and others like him, andhe is not taking anything away from anyone. Doc Bob simply believes he 1) joined the army, 2) went to war and fulfilled his service obligations, and 3) nothing is due him for it.

This heroic and sick medic would repeat this mantra to me many timesover the week he was here. One night I asked him about the contract he signed. You know, that contract we all signed at some enlistment office when a sergeant in pressed fatigues gave us the paper and pen to affix our names. We knew we might go to war and we knew we might die or be maimed for life. That was acceptable to us. But, that's all we knew, and that starched fatigues sergeant didn't tell us about the other conditions of the contract.

I asked Doc Bob if he were aware of those other conditions of the

contract. He said he was not. I then began to cite some of those

conditions to him and asked him would he have signed that contract

knowing they existed. Just some of those unwritten conditions I rattled off to Doc included:

**You may experience depression for the rest of your life and will

need to be on medication just to live somewhat of a normal life.

** Your parents and siblings may be emotionally tortured during

your time at war and beyond.

**You may live a life of paranoia, trusting few or no one.

**You may be socially restricted, fearing the outside world and

spending most of your time in your bunker at home.

**You may be emotionally dead; it don't mean nothin'.

**You may experience regular nightmares and dreams which frighten you and your wife, resulting in sleeplessness which can cause other physical and mental maladies.

**You may marry twice, thrice or more times, or remain unmarried,

because no one understands you and cannot live with your mood swings, violence or threat of violence.

**You may alienate your sons and daughters, perhaps to never again

re-establish mutual love and closeness.

**You may ponder the thought of suicide, as many of those you

served with did more than ponder that act.

**You may live with guilt for acts you committed or didn't commit,

the slightest sight or smell activating that guilt at the least

opportune times.

**You may lose most or all of your pre-army friends because you've

changed, you will never again be the person you were before your

army/war experience.

**You may religiously lock all your doors, rechecking them, and

keeping a weapon or weapons close at all times in case of an attack.

**You may find yourself in fights with strangers, friends and even

relatives, and then hate yourself afterwards.

**You may smother your wife and kids with your "protection",

making their lives miserable.

**You may lose your god or other beliefs formerly important to

you.

**You may adopt rituals, rituals not normal to others, and they

will be part of your daily routine.

**Going to a movie or a restaurant with your bride is a major

struggle or something you just don't do. Too many strangers out there, it's unsafe out there.

**You may cry way too often, sometimes just sitting alone and

thinking.

**If you do socialize at all, it might be at some dungy VFW filled

with smoke and belching vets. You feel safe there. Of course, this

does not appeal much to your wife.

**You may take risks, physical risks and others, afterwards

wondering why the hell you did that.

**You may be a womanizer, a boozer or a drug user, all to hide

some deep pain you don't quite understand.

**You may only be able to hold a job where you work alone because

you can't work with others. Or, you may not be able to work at all.

**Every one of these symptoms add up to stress. And stress is the biggest killer of all. PTSD is not being crazy, PTSD is living a life of

stress.

I then asked Doc Bob if he would have so readily signed that contract

many years ago had they told him about these possible conditions. He honestly replied, he wasn't sure.

These "conditions" of that contract we all signed were never written,

there was no second page to the contract, they were simply little

bonuses many of us were given by the army as we excitedly headed off to Basic somewhere. And, many of these gifts are better known at Post Traumatic Stress. Our brains have been taught to act and react

differently than what is otherwise considered normal. And what was

taught us and what we experienced at war can never be unlearned, it can only be managed.

Doc Bob earned his disability rating, he is sick. His view of nothing

is owed me, is unjustified. He is no different than the kid coming home from Iraq with no leg. The only difference is, the kid can see his wound; our wounds are hidden inside and difficult to understand and accept.

"I WAS THERE LAST NIGHT..."

By Robert Clark

PO Box 457

Neillsville, WI 54456

A couple of years ago someone asked me if I still thought about Vietnam. I nearly laughed in their face. How do you stop thinking about it? Every day for the last twenty-four years, I wake up with it, and go to bed with it.

But this is what I said. "Yea, I think about it. I can't quit thinking about it. I never will. But, I've also learned to live with it. I'm comfortable with the memories. I've learned to stop trying to forget and learned instead to embrace it. It just doesn't scare me anymore."

A psychologist once told me that NOT being affected by the experience over there would be abnormal. When he told me that, it was like he'd just given me a pardon. It was as if he said, "Go ahead and feel something about the place, Bob. It ain't going nowhere. You're gonna wear it for the rest of your life. Might as well get t o know it."

A lot of my "brothers" haven't been so lucky. For them the memories are too painful, their sense of loss too great. My sister told me of a friend she has whose husband was in the Nam. She asks this guy when he was there. Here's what he said, "Just last night."

It took my sister a while to figure out what he was talking about.

JUST LAST NIGHT. Yeah I was in the Nam. When? JUST LAST NIGHT. During sex with my wife. And on my way to work this morning. Over my lunch hour. Yeah, I was there.

My sister says I'm not the same brother that went to Vietnam. My wife says I won't let people get close to me, not even her. They are probably both right.

Ask a vet about making friends in Nam. It was risky. Why? Because we were in the business of death, and death was with us all the time. It wasn't the death of, "If I die before I wake." This was the real thing. The kind where boys scream for their mothers. The kind that lingers in your mind and bec o mes more real each time you cheat it. You don't want to make a lot of friends when the possibility of dying is that real, that close. When you do, friends become a liability.

A guy named Bob Flannigan was my friend. Bob Flannigan is dead. I put him in a body bag one sunny day, April 29, 1969. We'd been talking, only a few minutes before he was shot, about what we were going to do when we got back in the world. Now, this was a guy who had come in country the same time as myself.

A guy who was loveable and generous. He had blue eyes and sandy blond hair. When he talked, it was with a soft drawl. Flannigan was a hick and he knew it. That was part of his charm. He didn't care. Man, I loved this guy like the brother I never had. But, I screwed up. I got too close to him. Maybe I didn't know any better. But I broke one of the unwritten rules of war.

DON'T GET CLOSE TO PEOPLE WHO ARE GOING TO DIE. Sometimes you can't help it.

You hear vets use the term "buddy" when they refer to a guy they spent the war with. "Me and this buddy a mine . . "

"Friend" sounds too intimate, doesn't it. "Friend" calls up images of being close. If he's a friend, then you are going to be hurt if he dies, and war hurts enough without adding to the pain. Get close; get hurt. It's as simple as that.

In war you learn to keep people at that distance my wife talks about. You become so good at it, that twenty years after the war, you still do it without thinking. You won't allow yourself to be vulnerable again.

My wife knows two people who can get into the soft spots inside me. My daughters. I know it probably bothers her that they can do this. It's not that I don't love my wife, I do. She's put up with a lot from me. She'll tell you that when she signed on for better or worse, she had no idea there was going to be so much of the latter. But with my daughters it's different.

My girls are mine. They'll always be my kids. Not marriage, not distance, not even death can change that. They are something on this earth that can never be taken away from me. I belong to them. Nothing can change that.

I can have an ex-wife; but my girls can never have an ex-father. There's the difference.

I can still see the faces, though they all seem to have the same eyes. When I think of us I always see a line of "dirty grunts" sitting on a paddy dike. We're caught in the first gray silver between darkness and light. That first moment when we know we've survived another night, and the business of staying alive for one more day is about to begin. There was so much hope in that brief space of time. It's what we used to pray for. "One more day, God. One more day."

And I can hear our conversations as if they'd only just been spoken. I still hear the way we sounded, the hard cynical jokes, our morbid senses of humor. We were scared to death of dying, and trying our best not to show it.

I recall the smells, too. Like the way cordite hangs on the air after a fire-fight. Or the pungent odor of rice paddy mud. So different from the black dirt of Iowa. The mud of Nam smells ancient, somehow. Like it's always been there.

And I'll never forget the way blood smells, stick and drying on my hands. I spent a long night that way once. That memory isn't going anywhere.

I remember how the night jungle appears almost dream like as the pilot of a Cessna buzzes overhead, dropping parachute flares until morning. That artifical sun would flicker and make shadows run through the jungle. It was worse than not being able to see what was out there sometimes. I remember once looking at the man next to me as a flare floated overhead. The shadows around his eyes were so deep that it looked like his eyes were gone. I reached over and touched him on the arm; without looking at me he touched my hand. "I know man. I know." That's what he said. It was a human moment. Two guys a long way from home and scared shitless. "I know man." And at that moment he did.

God I loved those guys. I hurt every time one of them died. We all did. Despite our posturing. Despite our desire to stay disconnected, we couldn't help ourselves. I know why Tim O'Brien writes his stories. I know what gives Bruce Weigle the words to create poems so honest I cry at their horri ble beauty. It's love. Love for those guys we shared the experience with.

We did our jobs like good soldiers, and we tried our best not to become as hard as our surroundings. We touched each other and said, "I know." Like a mother holding a child in the middle of a nightmare, "It's going to be all right." We tried not to lose touch with our humanity. We tried to walk that line: To be the good boys our parents had raised and not to give into that unnamed thing we knew was inside us all.

You want to know what frightening is? It's a nineteen-year-old-boy who's had a sip of that power over life and death that war gives you. It's a boy who, despite all the things he's been taught, knows that he likes it.

It's a nineteen-year-old who's just lost a friend, and is angry and scared and, determined that, "Some asshole is gonna pay." To this day, the thought of that boy can wake me from a sound sleep and leave me staring at the ceiling.

As I write this, I have a picture in front of me. It's of two young men. On their laps are tablets. One is smoking a cigarette. Both stare without expression at the camera. They're writing letters. Staying in touch with places they would rather be. Places and people they hope to see again.

The picture shares space in a frame with one of my wife. She doesn't mind. She knows she's been included in special company. She knows I'll always love those guys who shared that part of my life, a part she never can. And she understands how I feel about the ones I know are out there yet.

The ones who still answer the question, "When were you in Vietnam?" with Hey, man. I was there just last night."

Nam Guardian Angel aka Kathie Costos DiCesare is a Senior Chaplain, certified, licensed, insured and ordained by the International Fellowship of Chaplains. Military Spouses of America, Board of Directors and coordinator of PTSD efforts. NAMI Veterans Council. Editor and Publisher of Wounded Times Blog. Consultant and speaker on what needs to be done for our veterans and families.

Kathie is determined to end the stigma of this wound and provide the knowledge to wounded veterans so they seek help as soon as possible. Kathie is married to a Vietnam Vet who came home with the wound of PTSD.

Kathie believes that marriages can survive and families can create their own kind of normal. After all, her marriage survived for over 24 years. She has been with her beloved Jack since 1982 and fighting for veterans ever since they met.

Kathie has created videos so that people can understand without having to read through clinical books and reports but gain the knowledge first hand. She has a free book, For The Love of Jack, His War/My Battle sharing what 18 years of our life was like as PTSD went from mild to all consuming and then toward healing.

Kathie shares the heartache and the faith that carried her through with the ability to forgive. Her husband was wounded and just needed help to heal. Look for the links to the videos and the free book right from her sites.

PMIM Outposts are lead by Christian Vets who care deeply about veterans and their struggles. They fully understand the difficulties associated with returning home after a long and difficult deployment as well as the non-combat experiences. Outposts are places for veterans to talk, share and listen to others who have walked in their shoes. All Vets are welcome regardless of what country they served with and gender is irrelevant as both men and women have served and sacrificed for their respective countries.

PMIM Homefront groups are lead by Christian mothers, wives and friends of both active duty military and veterans. They provide an understanding ear and caring heart that only those left behind at home can understand. They have experienced the stress of dealing with deployments and the effects of a loved one returning home from war. If you have someone you love deployed or having issues readjusting since coming home get connected with a local group or contact HQ for assistance.

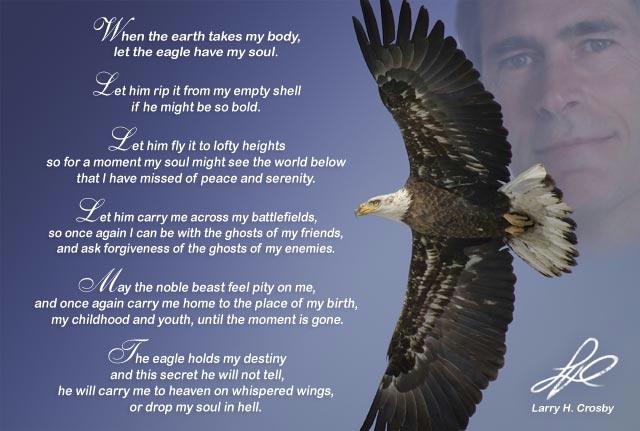

The author of this poem, Larry Crosby, was a Vietnam Veteran from South Dakota that died from Agent Orange cancer many years after his tour of duty in Vietnam.

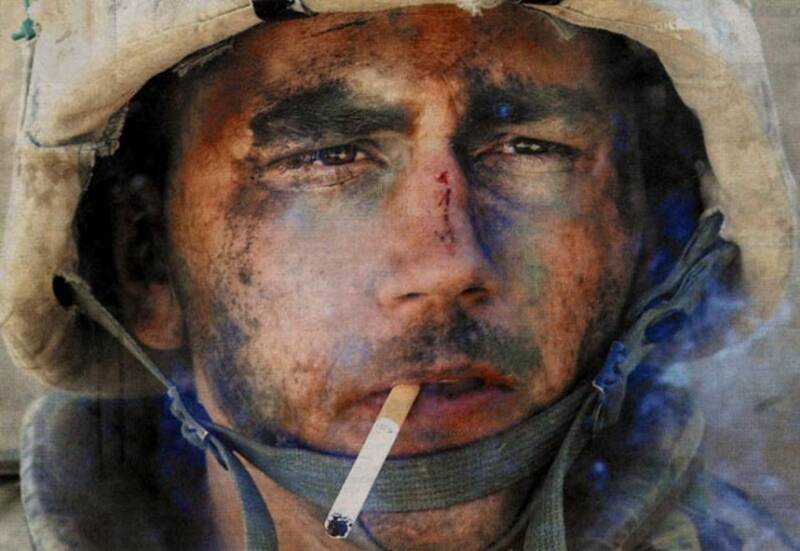

PTSD ... Not all wounds are visible

Powerful Writings Of Ones That Live With The Invisible Wounds

"If you can hold someone's hand, hug them or even touch them on the shoulder, you are blessed because you can offer God's healing touch."

Visit Monica's site to learn more about her mission & her

***Please click on the this link below & listen as you visit***